Canons and Canon Fodder

There are no “must read” books

Dec 9th 2016

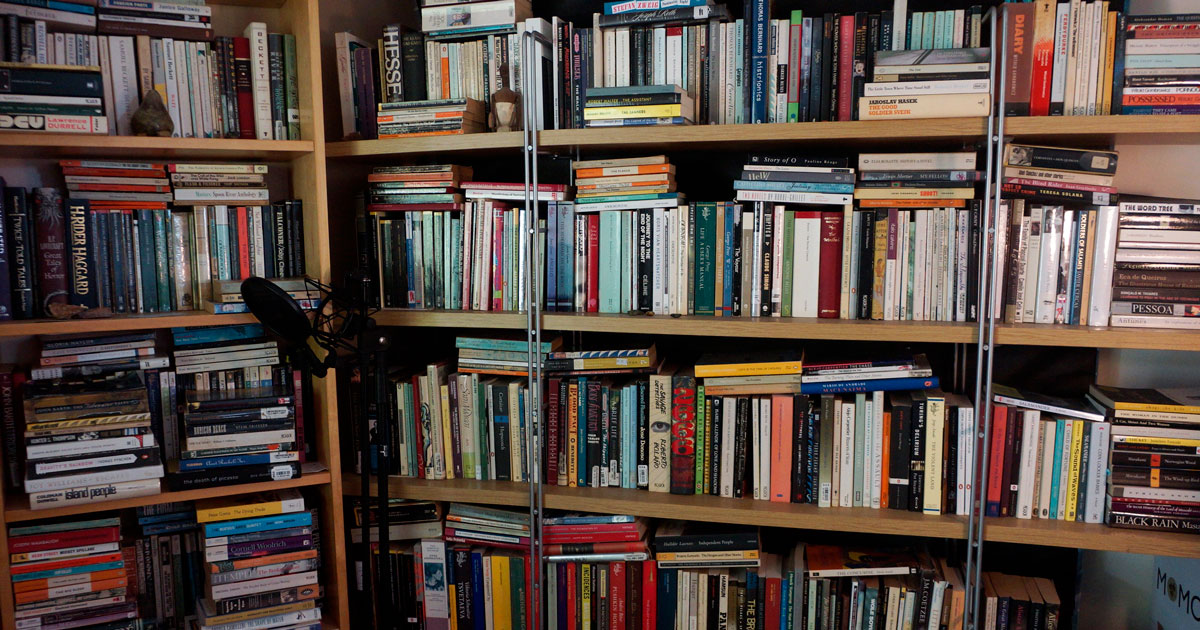

“The idea that there exists such thing as a ‘must read’ book is one of the great fallacies diluting literature. To judge a reader unfavourably because a certain book is not on his or her shelf, rather than to praise and learn from the idiosyncratic choices to be found there instead, is to wish for a literature of bland homogeneity.”

I wrote this four years ago, and thought of it again today. Today, I think, I believe it still more.

I awoke this morning to shock at the news of Donald Trump’s victory in the U.S. election. My first thought was of the possibility of Trump’s being assassinated, but then I remembered that peace-loving leftists don’t assassinate people (and that, therefore, violence can never serve a peace-loving leftist revolution). My appetite for political analysis thus temporarily assuaged, I followed a train of thought that led me to literature.

I thought of John F. Kennedy, and of Don DeLillo’s Libra (his novel of the Kennedy assassination) and whether or not I’ll ever read it (I’ve read two DeLillo’s – White Noise and The Body Artist – and enjoyed neither), and then of Thomas Pynchon, William Gaddis, Donald Barthelme and what I might call the postmodern American canon, and of how some fans of said canon of my acquaintance preach the philosophy of “must read” and look down their noses on anyone who has not read plentifully from this canon.

As someone who has long been fascinated by literature in translation, I’ve been known to rant against Anglo publishers, booksellers and academics for their fidelity to their inevitably Anglo-centric canons. I’ve learned to distrust the taste and recommendations of anyone whose bookshelves resemble a university reading list, unless that reading list is infiltrated by idiosyncrasies revealing a true, personal love of reading, and a passion for discovery. And yes, at this stage I’d distrust anyone whose shelves resembled the DeLillo and co. canon too, unless those shelves held a few preferably non-Anglo surprises.

I hope I’m not stressing the translation thing too much. Works in translation are one area of literature under-represented in Anglo criticism and publishing. There are others: works by women, “genre” works, short stories and novellas, comics. The important consideration to me, when surveying a person’s or bookshop’s shelves, is whether I see a personal quest or passion in the selections – if so then, whatever that passion might entail, I trust and am made curious by it; I want to learn more. The DeLillo club, once upon a time, might have resembled someone’s personal passion. Before it was codified and made gospel, a shelf full of the now-usual American postmodern suspects might have made me curious as to its curator, but nowadays I know no curation is necessary; it’s a reading list, a topic of study. And that’s fine – please, study what you like, but don’t tell me I “must” study it too, and don’t presume if I haven’t studied it I’m ignorant.

For me, the key transformative texts and writers in my reading are, in the rough order of my discovery of them:

William Golding: The Inheritors, Pincher Martin, The Spire

George Orwell: 1984

Albert Camus: The Outsider, The Plague

Hermann Hesse: The Glass Bead Game, The Journey to the East, Knulp

Kurt Vonnegut: Slaughterhouse Five

Milan Kundera: The Unbearable Lightness of Being, The Joke

Gabriel García Márquez: One Hundred Years of Solitude

Jorge Luis Borges: Labyrinths

Edgar Allan Poe: The Fall of the House of Usher & Other Writings

Franz Kafka: The Castle, The Trial, Metamorphosis, short stories

Fyodor Dostoevsky: Crime and Punishment, The Idiot

Nikolai Gogol: short stories

Patrick McCabe: The Butcher Boy

Knut Hamsun: Hunger, Mysteries, Pan

Witold Gombrowicz: Pornografia

Georges Bataille: Blue of Noon, The Story of the Eye

Pauline Réage: The Story of O

Jack London: The Call of the Wild

Margaret Craven: I Heard the Owl Call My Name

Raymond Chandler: The High Window, novels, stories

Dashiell Hammett: The Maltese Falcon, Nightmare Town

Chester Himes: Cotton Comes to Harlem, the Harlem novels

Robert Walser: short stories, The Robber

Anna Kavan: Julia & the Bazooka

Natsume Sōseki: Kusamakura, Light and Darkness, The Gate

Masuji Ibuse: Salamander & Other Stories

Unica Zürn: Dark Spring

Alfred Jarry: Ubu Rex

Raymond Carver: short stories and poems

Haruki Murakami: The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle

Jim Thompson: A Hell of a Woman, novels

Antonio Tabucchi: Requiem, Pereira Declares, Vanishing Point, Indian Nocturne

Fernando Pessoa: poems and The Book of Disquiet

José Saramago: The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis

Anna Akhmatova: poems

Samuel Beckett: Watt, Molloy, The Unnamable, Nohow On

Thomas Bernhard: novels

Michael Manning: Hydrophidian

David Goodis: Shoot the Piano Player, the noir novels

Walt Whitman: Leaves of Grass

Charles Burns: Black Hole

Roberto Bolanõ: 2666

Jean Giono: The Horseman on the Roof, Two Riders of the Storm

Tarjei Vesaas: The Birds

Juan Rulfo: The Burning Plain & Other Stories, Pedro Páramo

Andrei Platonov: The Fierce and Beautiful World

Peter Guralnick: Last Train to Memphis & Careless Love

Miles Davis: Miles: The Autobiography

Alvaro Mutis: The first three Maqroll novellas

Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky: The Letter Killers Club

Julia Voznesenskaya: The Women’s Decameron

Javier Cercas: Soldiers of Salamis

Willa Cather: Death Comes for the Archbishop

Hermann Melville: Bartleby the Scrivener

Denis Cooper: Closer, Frisk

Felisberto Hernández: Lands of Memory, Piano Stories

Christoph Meckel: The Figure on the Boundary Line

Tadeusz Borowski: This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen

Kazuo Koike & Goseki Kojima: Lone Wolf and Cub

Nik Cohn: Awopbopaloobopalopbamboom

Clarice Lispector: The Passion According to G.H.

Tor Ulven: Replacement

René Daumal: Mount Analogue

Sherwood Anderson: Winesburgh, Ohio

Gerald Murnane: Barley Patch, A Million Windows, Landscape with Landscape

The attentive reader will notice only one Australian author on this list: Gerald Murnane. In a way, Murnane’s story is a good example of why I distrust the forces behind canonisation. For years (since my late teens and early twenties, when I first read Murnane’s “The Only Adam” in anthologies and saw his most successful novel, The Plains, in secondhand bookshops, and heard him eulogised by my then-editor Jenny Lee), I’d tried and failed to like him. I’ve owned at least two copies of The Plains over the years, and started reading it on at least three occasions, but it bored me – it still does, if my attempt of 1-2 years ago is any indicator – and Murnane’s own opinion of it concurs just as much with mine as with the prevailing critical opinion. As to “The Only Adam”, which would seem to be (or to have been) his most popular story, it’s pretty ordinary. Why was it the Murnane story to be most anthologised? Because it’s the only one most casual readers were likely to understand, or to be bothered reading beyond a few paragraphs; or (just as likely) it’s the only one most editors and publishers thought most casual readers would understand. And I’m willing to bet The Plains has been canonised for much the same reason, and because it attempts to articulate something grand and sweeping about “The Australian Identity”, a crucial aspect of any work that’s going to be upheld by the Australian arts funding and prize-giving and canon-making establishment.

So for twenty years I rated Murnane a curio and not much more, till I read Barley Patch two years ago. Now I’m sifting back through his oeuvre (avoiding everything pre-The Plains), and I’m astonished at what I’ve found there. Maybe, ultimately, Murnane’s own reputed favourite, Landscape with Landscape, will be canonised, once a broader public reads him and decides The Australian Identity isn’t so crucial after all. Meantime, I’m unlikely to prick up my ears to anyone discussing The Plains without referring to his other books. Just think if I’d taken them all seriously and forced myself, with gritted teeth, through The Plains; I might never have discovered A Million Windows and had my mind blown.

I’ll say it again: There are no must-read books.